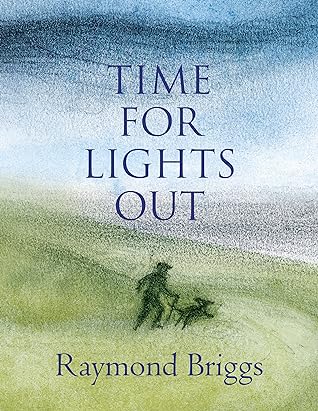

Time For Lights Out by Raymond Briggs

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I have been thinking about how to begin this review and I have failed, several times, because I’m not quite sure what to say about this. So perhaps we shall begin there and tell you about my doubts and we shall see if we can find a way out of that somewhere. I think the first thing to note is that I would not call this a graphic novel. I’m not sure what I would call it but I know I wouldn’t call it that. Perhaps an illustrated poetry collection? But then, not all of it is poetry. It’s more of a scrapbook, a kind of dialogue between Briggs and the world (and his kind of alter-ego, a provocative and questioning character called ‘Prodnose’) but even then, even this doesn’t really come to capture this strange and challenging book which is all of these things and yet somehow none of them.

I think, perhaps, Time For Lights Out is this: the story of somebody who has spent their career writing about humans (and humanity) now trying to figure out how reckon with their own human-ness functions in the middle of this. Writing is personal. It is always, really, about people and who they are and why they do what they do and if your work, if your life-work is about people, if you have spent years seeing then it is inevitable at some point, you must figure out what you see when you turn your lens upon yourself.

So then, this is about people, let us lock that in, and although nominally this is about age and older people, at its heart, I think, this is an exploration of the great unknown. Because there are parts of life that we cannot write about, cannot capture, because we will simply not be there to capture them or to write back and tell others about how it went. Death then and dying, in this book, becomes something ever-distant, able to be understood and rationalised only by looking at the space around it for the thing itself remains unknowable, unintelligible.

But maybe then, that’s how we understand that last great unknown, we understand the space around it, the looks towards it, the counter-balances and pre-echoes of it (pre-echoes? such a thing? yes, we shall have it) that occur throughout our life. Our embrace of mortality. Our recognition of this. For Briggs, mortality comes in the domestic, in the heirlooms he has inherited from his parents and in the quiet shift of life around him. The routine of going to bed. The dog walk. The fox laid dead on the road. The grave with cyclamens on it in the churchyard. The small and acute detail of it, the known.

This isn’t a happy book but occasionally it is raw with love and joy. It’s contradictory, and it’s occasionally distasteful (there is one moment in particular that sat rather uncomfortably with me), but I do think it’s an honest, uncompromising thing. Some of the artwork is incredible and so brilliantly done and yet others are light, unfinished things, and while I did not like this kind of … impenetrability? unknowability? … to the latter. Briggs has spoken about this in an interview (most particularly here in this Guardian piece ) and described it as a “work in progress”. (but then, in a way, aren’t we all, who am I to ask for this to be finished when the raw, ragged edge might be precisely what it needed to be).

If this is the final breath of a remarkable career then it is a powerful, poignant, thing. It is also an occasionally frustrating thing, a deeply irrascible thing, a fiercely independent thing, and as much as it wants to be read, it is deeply annoyed by that. A paradox, then, a grumpy one, an incredible one.

View all my reviews

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.