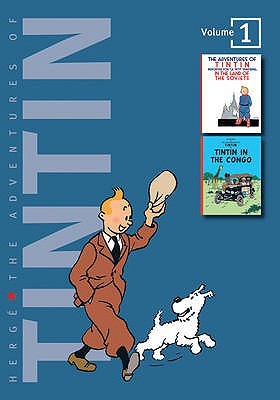

The Adventures of Tintin, Volume 1: Tintin in the Land of the Soviets / Tintin in the Congo by Hergé

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

A small, neat bindup edition of the first two Tintin adventures: Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin In The Congo, this is a complex thing to review. At one level, we’ve got an artist beginning to figure out who he is and what he can do and at the other, we’ve got some frank, horrible racism and colonialism and the shooting of anything that moves. And yet, this isn’t new space for me as a reader: I read a lot of books from times when attitudes were not great about anything other than the white, european man, and I can work with that (literature is a product of time and place, it reflects – rightly or wrongly – the world in which it is born and the people it seeks to serve, I think), but both of these bothered me and Tintin In The Congo, in particular, is something genuinely distasteful at a thousand different levels.

And I was trying to figure out what that was, why there was that difference here for me in terms of reading this and say somebody like Bessie Marchant at her most Bessie Marchentiest or Capt W E Johns at his Bigglesiest, and I think that the form of story plays a part here. These are comic strips and Congo is in colour and I think there’s an immediacy there, when you have the visual right in front of you and you literally cannot escape it. That is the great wild power of the comic and also, sometimes, its greatest weakness. You can’t hide from it when it’s there on the page. And what was on the page, the brutal 1930s attitudes of raw colonial might, the way a young Belgian artist might view the Congo, is very difficult to see here. The publishers do include a foreword from the translators to Tintin in the Congo which recognises some of these issues. It is slightly coy in its phrasing and I would have welcomed something a little bit franker here. It also mentions the redrawing of page fifty-six but the page-numbering of this edition does not match this.

I’ve spoken mainly about Tintin In The Congo here so what about Tintin In The Land of the Soviets? It’s in black and white and much more approximate; there’s a rough, readiness here that is interesting to compare against much later titles – even Tintin In The Congo. It’s very jingoistic, as they both are, and Tintin is literally the toughest person ever. He survives an enormous amount of murder attempts (so many they almost become a little? repetitive?). Snowy is instantly the brains of the operation but honestly, after he defrosts a frozen Tintin with the aid of a handy packet of salt, you kind of have to just sit back and go “look, just do your thing, I cannot stand in your way”.

So then, this is this; a messy, racist, colonialist, violent thing that isn’t remotely “good” at any level (such a subjective statement! forgive me!) but it is something that I do think should still be read. I recognise my privilege in being able to say that as well. I think if you can critically read something like this and support others to read it critically as well and be able to figure out your reactions and understanding of it in a critical fashion, then that is productive. If we accept that literature for young readers, indeed all literature, is political (and we should), then we can also accept that reading can be political and an act of power, of agency, of making your own narrative when the ones about you are so very lacking.

View all my reviews

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

I think those two titles in the series are for completists only. I grew up with the Tintin books and loved them (even though I wasn’t supposed to because I was a GIRL- I read my first one when staying with a boy cousin of my own age). They get much more broad-minded later on; I always loved Tintin in Tibet, for example. But I really liked your comment/observation about the fact that they are visual, especially when coloured in as in Congo, making them seem more awful than other casually racist works of the period or earlier.

Oh! I have Tintin in Tibet coming up soon – I’ll look forward to that.

Critical reading indeed is required, and not the flippant putdown that ‘critical’ too often implies but deep assessment and interpretation, good as well as bad. What you say about the Tintin stories at the start – Tintin as a kind of ordinary Superboy, villains as totally evil, bystanders as stupid, hazards as predictable in their repetition – is largely true of the later instalments too but marginally less offensively; all of it predisposed me to prefer Astérix for all that I loved the art and colours of Hergé’s panels.

I remember reading a lot more Asterix than I did Tintin – I don’t know if that’s simply because we were more of an Asterix household than Tintin. But I do think that, after having read these, there’s something different in their respective treatments of physicality and violence. Tintin, so far, has a very (very) unreal sense of the physical but Asterix – even with its sense of unreal physicality – feels a lot more grounded. It will be interesting to see how things change the more I go through the series.